Bar Ilan University, Israel

|

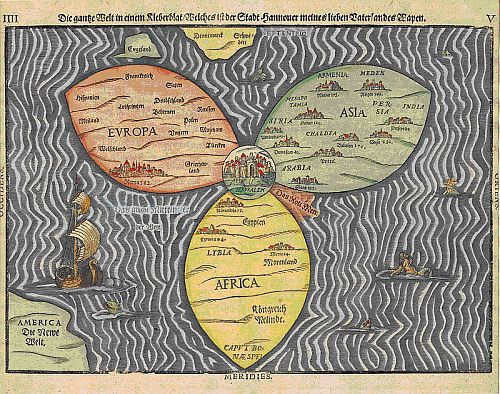

Hanging on the west wall of my living-room in the Old City of Jerusalem is a very famous map by the Protestant theologian Heinrich Buenting of Hannover (1545-1606). It appeared as a woodcut in the Itinerarium Sacrae Scriptura, published in Magdeburg in 1581, and symbolically presents the world in the form of a three-leaved clover, with Europe and Asia on the top left and right, Africa centered below, and so, in the middle of the "map", at the point from which the three leaves – continents converge-emerge, within a circle – a symbol of unity and perfection – is Jerusalem and the Holy Temple.

Jerusalem in Western thought was regarded as the ideal city, and the Hebrew for the latter part of the name Salem – Shalem, means completeness, perfection. And it is surely not by chance that it is encased in a circle, rather than a square, bearing in mind that in the Revelation of St. John, Jerusalem is described as a city with twelve gates on a square plot of land, and several roughly contemporary maps, such as these of Adrichom have Jerusalem in a rectangular format. And Buenting himself, in another map, has an oblong Jerusalem. Thus symbolically Jerusalem and the Holy Temple constitute the ideal focal point from which the sacred spirit radiates throughout the whole World. Of course, Buenting's three-leaved clover theme was also the trefoil arms of the city of Hannover, and indeed the superscription mentions Hannover as his beloved homeland. However, some have suggested that this formal may also allude to the Trinity. Maybe the artist-theologian had both allusions in mind. Be that as it may, probably a more historically and theologically accurate portrayal of the evolutionary development of the three monotheistic religions – admittedly a theme not intended by Buenting – would better be repjresented by a tree, with its trunk representing biblical Judaism, out of which spring two branches, rabbinic Judaism and Christianity, and a third branch higher up on the thinner branches continuation of the trunk, Islam. But the Buenting map does reflect an accurate actuality, wherein the three major monotheistic religions all converge at Jerusalem. That point of convergance, Beunting's circular cartouche, can be a tinder-dox awaiting a flash point of conflagration, or an island of harmonic cooperation. While the Temple Mount might be an area of controversy between Judaism and Islam, there are relatively few "danger areas" in Jerusalem between Christianity and Judaism, and likewise not between Islam and Christianity.

Nostrae Aetate, and its theological progenies, has already paved the way to a new and deeper harmonious relationship between Catholicism and Judaism, in a innovative theological understanding of their "intra-filial" consanguinity. Historically, the rift between Islam and Judaism was never so theologically great as was that of Christianity and Judaism in the past. Hence, the move towards greater mutual appreciation and a lessening of inter-religious tension should be easier for Islam than it was for Catholicism, at any rate at a religious level. But regrettably, politics has intervened, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has morphed into a Judaism-Islam conflict. And a radicalizing trend in Islam, in many countries and communities, has extended this conflict into the realm of Christendom and politically against the Christian West. Furthermore, Islam itself is split into contending sects, fightly over territorial and ideological dominion.

Thus, there is a confluence of a variety of explosive elements, territorial controvercies of a micro (Temple Mount) and macro (Middle East) nature, national conflict (Israel-Palestine), theological dissent (intra-Islamic and inter-religious), etc. Areas of disagreements between Judaism and Christianity have been greatly minimized, while areas of discord between Judaism and Christianity on the one hand and Islam, on the other, have been disproportionately magnified – and this, somewhat ironically, despite the fact that theologically in so many ways Judaism and Islam are much closer than Judaism and Christianity.

Of course, there are liberal elements in Islam that can conduct a cultured and respectful dialogue with other religions. But their voices are muted in comparison with the militant fundamentalists.

Within the turbulent Middle East, Israel is an island of relative calm, in which all religious denominations find their rightful legal place and complete freedom of practice. That does not mean that there are not areas of contention and disagreement, but they can be – and indeed are – mediated in good faith. Extreme elements in each faith will seek to upset the balance and sew discord, but they are usually peripheral groups and the security forces are designated to deal with them. So within the extremely complex volatile and highly tormented world of religious conflict, which includes world terrorism, international defamation and delegitimation after most invidious nature, Buenting's cartouched Jerusalem should and could be a venue for constructive dialogue, between mutually appreciative religious representatives, who are fully aware of the enormous dangers of "wars of religions", and who seek both a theologically and a pragmatic Modus Vivendi leading to a peace and harmony for which all well-wishers truly yearn. And in this way will the prophecy of Isaiah be fulfilled, as he wrote (56:7):

"Even them will I bring to My holy Mountain and make them joyful in My house of prayer: … for mine house shall be called a house of prayer for all people."

|